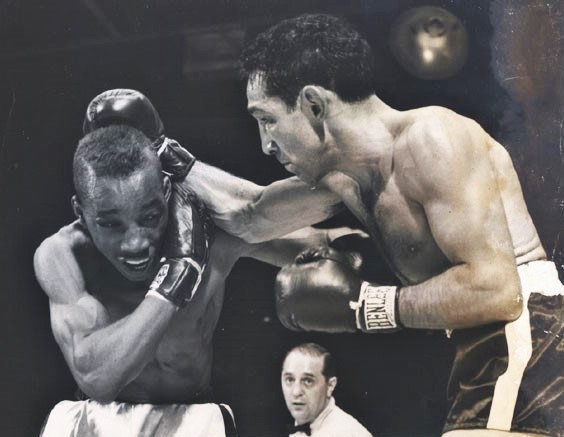

When James J. Jeffries, heavyweight champion of the world, retired undefeated in 1905, few were in any doubt that they had just seen the greatest heavyweight fighter of all time pass into legend. Lightweight champion Willie Ritchie, light heavyweight champion Jack Root, and heavyweight champions “Gentleman” Jim Corbett and Tommy Burns, all held that opinion, as did Joe Woodman, manager of the great Sam Langford. Indeed Langford, who traveled the length and breadth of the country campaigning to fight anyone, wanted no part of Jeffries in the ring.

But in 1910, “The Boilermaker” had allowed himself to be baited back into the ring by the disgraceful racial demagoguery of Jack London and others, who could not abide a black heavyweight champion in Jack Johnson. In their ensuing bout, Johnson pulverized the former champion with juvenile ease until his manager threw in the towel in the 15th round. Jeffries had prostituted his legacy chasing after a pointless, unachievable vision, and he knew it. “I could never have whipped Johnson at my best,” the former champion said. “I couldn’t have hit him. No, I couldn’t have reached him in a thousand years.”

Despite this, in 1971, six decades after Jeffries retired, Ring Magazine founder Nat Fleischer still had him ranked in the top two heavyweights of all-time. But consensus had shifted, and when Fleischer died a year later, it would have been difficult to find advocates for Jeffries’ supremacy; “apologists” would be a more fitting term.

In the last several years we’ve seen a number of high-profile retirements. Wladimir Klitschko, Timothy Bradley, Miguel Cotto, Juan Manuel Marquez, Shane Mosley, Andre Ward, James Toney, Roy Jones Jr., and of course, Floyd Mayweather Jr., have all moved on. These men had come to define, if not dominate, their respective divisions for the last decade or more. Some withdrawals, like Ward’s, seemed premature; others, like Cotto’s, timely; and at least one – Roy’s – far too late. (Perhaps the same should be said of Toney’s; he went 11-6-3 following his marvelous decision victory over Vassily Jirov to land the cruiserweight title in 2003. But his prodigious physical mass, impassable defence and sturdy chin meant you rarely feared for his well-being the way you did Roy’s.)

Sometimes legacies take a while to dissipate or accumulate; other times, it happens almost immediately. Two off this list already illustrate, in impasto palpability, the vicissitudes of time and posterity, to such an extent that we seem to be living in a different reality after their respective retirements than we did before. But one has benefited, while the other has suffered, from this sea-change.

In 2015, Roy Jones Jr. cut a pitiable figure. For his first fight in his adopted country of Russia, the once darling of the American sports scene took on former WBO cruiserweight champion Enzo Maccarinelli. I do not mean here to denigrate Maccarinelli; until his 2007 banger with David Haye diverged both men’s fortunes in opposite directions, he was an exciting and competent fighter with excellent punching power. But he would never have made it onto Jones’s radar at the Russian-American’s peak, and eight years and five KO losses later, he was barely a gatekeeper.

That he knocked Jones out was bad enough, but the manner of the finish – Jones free-falling face first after Maccarinelli had been able to tee-off at will – punctuated what a terrible state “Captain Hook” was now in. The fact Jones did not immediately retire after the match would have been shocking had he not ignored all pleas to call it a day since his brutal knockout loss to Antonio Tarver over a decade before. The once good ship Roy spluttered on for two more years and four inglorious fights before those pleas were finally heeded and harbour was mercifully made.

But as Jones himself once put it, “y’all must have forgot.” As soon as Jones was no longer an active fighter, boxing observers and insiders began to discuss his legacy with the benefit of hindsight for the first time. And a strange thing happened. Pleas became panegyrics and howls of anguish hagiographies; it was as though the years of ignominy had never happened.

Memory is an odd thing. As terrible as he was ten-plus years after his prime, that’s how good “RJJ” was at his best, something the valedictory highlight reels underlined. This was, after all, the man who shut out (an admittedly aged) Mike “The Body Snatcher” McCallum; who beat a prime Bernard Hopkins single-handedly (literally: Jones went into the fight with a broken right); who bewildered and battered the great James Toney (the last time for a long time Jones would go in as the underdog), who played a professional basketball game the morning of a middleweight title defence (which he won by knockout).

After seeing Jones whip Vinny Pazienza, the writer Budd Schulberg, who had grown up watching Benny Leonard and Lew Tendler at the Garden and could tell you anything you wished to know about Fritzie Zivic, Archie Moore, or Tony Canzoneri, compared Jones’s ability to that of Henry Armstrong and Sugar Ray Robinson. And this was before Jones became the first middleweight since Bob Fitzsimmons to win a heavyweight title and the first man in history to do it from light-middleweight.

Jones’s lack of basic defensive skills and boxing fundamentals meant he couldn’t protect himself once his relativistic speed left him, and time can only tell what damage Jones has done to himself by taking hundreds of additional unnecessary punches. But as of 2018 his legacy appears unassailable. After all, Ray Robinson, Muhammad Ali and Roberto Duran fought on too long, and we don’t hold it against them. The only mark against Jones, and what keeps him out of the elite category of those men, is the lack of competition he had in his prime, something Schulberg and others noted then. He was “as far ahead of his field as Seabiscuit,” although the polymathic Jones once rapped: “They got the nerve to say I ain’t fight nobody – I just make them look like nobody.” Consider the careers Toney and Hopkins had after Jones made them look average.

By contrast, up until his absurd fiasco with Conor McGregor, Floyd Mayweather Jr’s stock as a historically significant fighter could not have been higher. Although very few subscribed to his boast of being “The Best Ever,” he seemed to have cemented his status as the greatest prizefighter of his generation by handily conquering Manny Pacquiao two years earlier, within months of Jones’s Waterloo against Maccarinelli. He’d beaten other future Hall of Famers, all-time greats, and even legends, often with relative ease; witness his victories over Juan Manuel Marquez, Canelo Alvarez, Arturo Gatti, Diego Corrales and Zab Judah to see the man at the peak of his uncanny powers. His conquests read like a who’s who of the divisions between light and middle for the last ten to fifteen years: Oscar De La Hoya, Jose Luis Castillo, Ricky Hatton, Shane Mosley. Best ever? No. But top twenty? Maybe.

Like Jeffries in 1905 and Rocky Marciano in 1956, Mayweather also retired undefeated. This meant far more to him than it had to them. Along with having defeated more title-holders in history, it’s the reason he gave for ranking himself above Leonard, Robinson, Duran and anyone else.

But pinning his legacy to that mast was a mistake. Unlike Jones’s, that estate seems to have atrophied since the day of his retirement. Firstly, lengthy win streaks are hardly unique in boxing. For example, Nino Benvenuti won his first 65 fights. Carlos Monzon went 80 straight without a defeat while Julio Cesar Chavez went 87-0. Willie Pep was 62-0 by the time of his first loss and then went the next 73 fights unbeaten before losing to the great Sandy Saddler. Going into his rubber match with Saddler, Pep was 152-2-1 after ten years in the ring. If Floyd had competed 155 times between 1996 and 2006, do you think his precious “0” would still be there?

When you pull at the threads of Mayweather’s record on its own terms, certain unravelings occur. The simple fact is that after “Money” took over from De La Hoya as the box office draw, the once “Pretty Boy” Floyd never really risked anything again. (Which is nothing to hold against him personally: why would you take risks, in a sport as dangerous as boxing, when you don’t have to?) Hatton was too small and tailor-made for a cultured counter-puncher like Floyd. Marquez had to move up to a catchweight Mayweather still couldn’t make, as he happily forfeited part of his purse to ensure Marquez had no chance. Mosley was too far from his prime and his lightweight best to really trouble his rival. In retrospect, the flat-footed Canelo was always going to be bamboozled by a matador of Mayweather’s class.

As for Pacquaio… well. For all Mayweather’s vaunted ability to navigate weight divisions, Pacquaio began at flyweight – six divisions below where Mayweather debuted – and had to load his pockets with stones to do so. That the Filipino once beat the holy hell out of one-time lineal middleweight champion Miguel Cotto – who Mayweather had no end of trouble with – is a division-hopping achievement worthy of Langford, Armstrong, and Jones. And if a boxer moving up and down in weight isn’t your thing, the consummate, vicious manner in which Pacquiao also defeated De La Hoya, Hatton, Mosley, and Antonio Margarito (whom Mayweather wanted no part of) means he’ll rank ultimately higher on all-time pound-for-pound lists than the Grand Rapids fighter, who must have thought he’d settled the matter in his favour in 2015.

If he wasn’t the best of his time, how can Mayweather claim to be the best of all time? As Max Kellerman has pointed out, when Roy Jones Jr was at his zenith in the late 90s, nobody put Floyd Mayweather at the top of their pound-for-pound lists. In 2001, when Mayweather delivered his career-best performance against Corrales, he was universally considered a worthy but distant second to Roy. Simply by retiring, Jones appears to have reasserted that gap after years of relative obscurity.

Posterity is a capricious mistress. But almost a decade since Mayweather’s valediction, she seems to be agreeing with R.A. the Rugged Man, who personally told Floyd he was special, but no more so than Aaron Pryor, Pernell Whitaker, or Emile Griffith. Meanwhile, I suspect that the further we get from Roy, the more superhuman he’ll look. Perhaps not in the league of Ray Robinson, but like Ray, he will always be a truly unique and epochal fighter, the type whose greatness imposes itself from the first time you watch him and ever after. — Laurence Thompson