From drunken drumming on stage next to Saïd Aouita to answering press conference questions from a songwriting great, the Jarrow Arrow looks back on a golden season 40 years ago

Looking back at Steve Cram’s world record-breaking summer of 1985, you could be forgiven for assuming that he was an athlete in peak physical shape. The reality was rather different and, instead, he spent the summer hobbling from one race to another while trying to deal with compartment syndrome in his calf muscles.

“I was hardly doing any training between the races,” he says. “The races were almost like training sessions.”

The then 24-year-old’s season began inauspiciously, with two DNFs. When he eventually got racing properly, his plans were sometimes dictated by the demands of television. “There was,” he admits, “no grand plan.”

Despite this rather imperfect backdrop, on July 16 of that year Cram became the first man to break the 3:30 barrier for 1500m during a thrilling victory over Saïd Aouita in Nice, running 3:29.67. In Oslo 11 days later he was the epitome of an athlete at the height of his powers as he stormed to 3:46.32 in the Dream Mile at the Bislett Games. Capping a memorable 19-day period, he showed his versatility by time trialling a world 2000m record of 4:51.39 in Budapest.

Yet the summer of 1985 was about much more than those three records. Even some hardcore fans forget that he won “another race” in Oslo at the end of June with the most comfortable-looking 3:31 for 1500m that you will ever see. At the Weltklasse in Zurich towards the end of August he defeated Olympic 800m champion Joaquim Cruz of Brazil over two laps in 1:42.88, a race that came just a few days after he also narrowly missed Seb Coe’s world 1000m record by a few tenths of a second on a blustery night in Gateshead, having been buffeted by winds in a gritty solo effort.

What’s more, there was even an end-of-season defeat in London at the hands of Steve Ovett to bring him back down to earth. “Thankfully people don’t remember that one as much,” he smiles.

It was a summer that saw Madonna and Wham dominating the music charts, Back to the Future was filling out movie theatres and a period when Brits only had four television channels to choose from.

With the BBC and ITV showing live athletics action sometimes several times each week, the public was virtually being force fed track and field, so it’s no surprise that the records and rivalries of Cram, Coe and Ovett have endured in the memory for so many years.

Somewhat appropriately, Cram now finds himself telling a new generation about the greatest athletes in the world via his current role as the BBC’s lead athletics commentator. From world record-breaker on the track, he is now the voice of the sport.

As I pick his brains about his remarkable 1985 season, I discover his sharpest memories aren’t necessarily of the races themselves. Instead he remembers being drunk and playing the drums in a noisy bar with Aouita in the wee small hours of the morning after their 1500m clash in Nice.

His clearest recollection of the 2000m record in Budapest, meanwhile, is Sir Tim Rice – the songwriter of Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita fame – piping up with a random question at his press conference simply so he could meet Cram to talk about their mutual love of Sunderland Football Club.

Cross country and Colorado

If Cram couldn’t train much during the summer of 1985, how did he build the strength to break all these records? The answer is that his fitness was created during the winter with gruelling cross-country races and his annual spring altitude trip to Colorado.

After being injured early in 1984, he managed to get himself in decent shape for the Olympics in Los Angeles – winning 1500m silver behind Seb Coe – and therefore went into the winter in good shape. This carried through the winter months as he notched up the miles in the North East of England under the guidance of coach Jimmy Hedley.

Cram also couldn’t resist dipping into local road and cross-country races, as he explains: “When I was a youngster, the measure of how well I was doing was initially racing cross country – the English Schools, Northern Counties, National and so on. I began to become a very good track runner and obviously that became the primary target and the main driver of what my training was about but I still had a lot of pride around my performance on the roads and cross country.

“Living up here in the North East at the time, if you ran a road race you were going to be running against, initially, Brendan [Foster], plus Micky McLeod, Charlie Spedding, Max Coleby and many others. Gateshead Harriers alone had a number of top internationals.

“So as I got into my early 20s and I was doing so well on the track, I still wanted to be competitive at the very least, if not win, when I turned out in a cross country or a road race. I’d particularly want to do well in road races. In cross country, I’d find that if the ground got muddy and slippy then I used to kiss goodbye to a good run.”

As Cram came into 1985 as the reigning world, European and Commonwealth 1500m champion, he got stuck into cross-country races to build endurance. One example was the Northern Championships in Thirsk, where he ran down the runaway leader, Carl Thackery – father of current international marathon Cali Hauger-Thackery to take the victory.

“The weather wasn’t great and there was a chance the races would be cancelled,” Cram remembers, “so I even went out the night before the race with friends, as I thought it wouldn’t be on.

“It did take place, though, with some of the course frozen solid like a road. Had that been a wet and soggy January day, there’s no way I would have won it!”

During this period of his career, Cram would go to Colorado for a few weeks’ altitude training. “I would have used altitude a lot more if I’d known then what I do now,” he says. “My winters weren’t always the same but I’d usually try to get a stint where I was somewhere warmer and then Easter time when I was at altitude in Colorado.”

Coming into the track season, however, his calf problems made training and racing difficult. After being beaten by Pat Porter of the United States in a 10km in Denver in early April, when he got home Cram dropped out of his own club’s six-mile road race in Jarrow and then didn’t finish in a 5000m at Gateshead while leading on the penultimate lap after feeling a twinge in his calf.

“I was having to modify some aspects of my training,” he explains, “and so doing a lot of very fast, hard running. I used to like that anyway, but I cut down on the mileage a little bit, I think, from 100 miles a week to around 80 miles a week but it was all very hard, fast running and a lot of high intensity training.

“I love when they talk now about athletes like Jakob Ingebrigtsen inventing double threshold. I’m like: ‘Yeah, okay, we were doing that a long, long time ago!’

“When I started the ’85 season, I knew I was in great shape, but I was having to nurse my calves. Every time I did anything like high intensity, such as a race, I was having to have a couple of days off. So that’s why I ended up with this plan to run a group of races together and then have a little bit of time off racing.

“I think a lot of people think I must have started that year with some kind of grand plan to run a bunch of records but it wasn’t really like that at all.”

Explaining the injury, he says: “What would happen with compartment syndrome is that it starts to really cramp up, particularly in a race scenario, and you start to get lots of micro tears. I was hardly doing any training in between the races. The races were almost like training sessions.”

Once into June, Cram opened his track season by finishing runner-up to Coe over 800m in a GB vs USA match in Birmingham. American Eugene Sanders led through the bell in 53.5 with Cram sitting at the back, but Cram began to move up on the second lap and was on Coe’s shoulder entering the home straight. Battling into the wind, Coe held off Cram in gritty style and the winner later remarked on their head-to-head record: “That makes it Chelsea 6, Sunderland 1!”

The race was live on ITV on a Friday evening as part of the television channel’s new deal to cover the sport and the 800m was the highlight of the meeting, with Ovett also in action, out-kicking Dave Lewis in the 3000m. The British middle-distance runners couldn’t prevent the United States from winning the overall match, though.

“I used to like starting with an 800m in a match like this,” says Cram. “In 1982 I’d started my season with a 1:44.4 win in an international match so from then on I liked starting the season with that distance in these kinds of matches.”

Cram admits his memory of that 800m isn’t too clear, but his recollection of the Oslo Games six days later is much better.

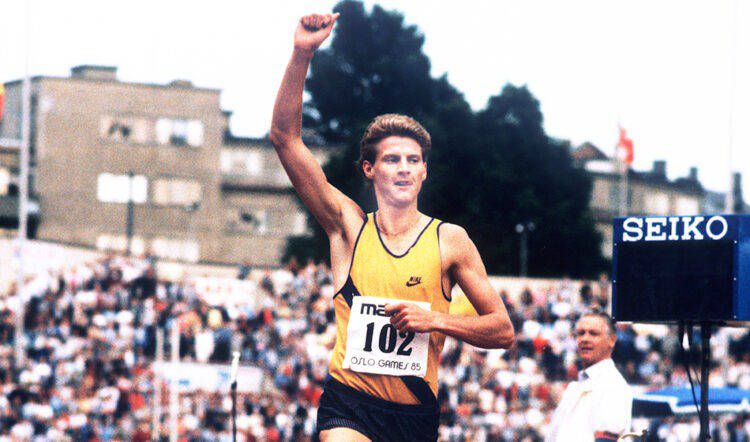

There, he led for the final 600m to clock 3:31.34 – the third-fastest time in history – to win by 3.24 seconds from Steve Scott and Jim Spivey of the United States. The world record at the time was 3:30.77, held by Ovett.

“It was the race that really gave me a sense of: ‘Wow, that felt way too easy’,” says Cram. “I think I ran something like a 53-second last lap off a reasonable pace against some good people like Scotty. I just remember thinking: ‘I can’t wait to get into my next race’. Everyone talks about the records but, in terms of how I felt, that was the easiest 3:31 I ran, by far.”

World record No.1 – Nice, 1500m, 3:29.67

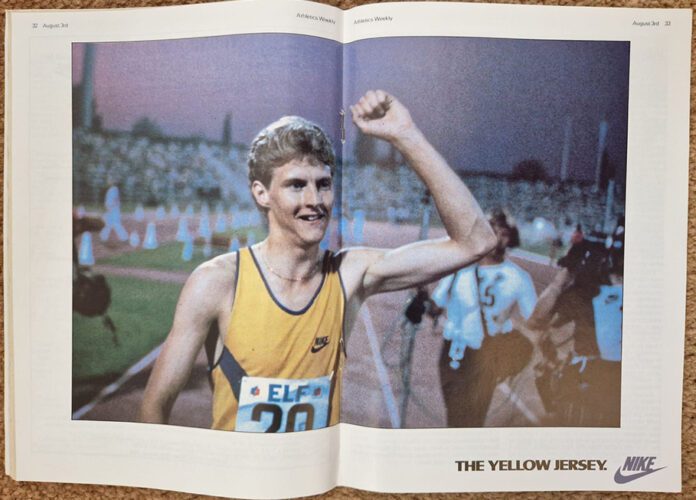

“Welcome, to the metric mile of the decade,” crackled David Coleman’s voice as the BBC’s coverage of the 1500m at the Nikaia Meeting in Nice began.

As it turned out, that remark was probably an understatement as the race produced one of the greatest 1500m races in history, with Cram and Aouita becoming the first men to break the 3:30 barrier as a stellar field, including Olympic 800m champion Cruz, finished in their wake.

The drama had begun a few days earlier, though, when Cram controversially withdrew from the 800m final at the AAA Championships in order to protect his fragile calf muscles ahead of the Tuesday night showdown in the south of France. In the back of his mind, he was also due to race against Coe at the end of the same week at the Peugeot Talbot Games at Crystal Palace. What’s more, there were no major championships to qualify for in 1985 so the AAA Championships was not a “trial” for anything.

Still, Cram felt pressured by the avid interest from television producers, as the AAA Championships was shown on ITV, so he decided to strike a compromise by running the heat but not the final.

“When ITV got the domestic athletics contract and paid quite a lot of money for it from the BBC after the ’84 Olympics, it was a big thing,” says Cram. “I told [the ITV presenter] Jim Rosenthal in advance that: ‘After the heats on Saturday you’ll have to come and interview me and I’ll tell you my legs are a bit sore and that I’m not coming back on Sunday’. So we had to contrive this interview after my heat. I said that I’d see how I felt in the morning and I’d try to warm up but I knew fine well I wasn’t going to.

“On the Sunday morning I had a bunch of guys like [promoters] Andy Norman and Alan Pascoe standing over me while I warmed up and then I said: ‘Nope, my calf’s sore, I’m not running’. They knew I was fibbing, although everyone did know I had a sore calf.”

Does Cram feel a bit guilty about this 40 years later? “I don’t at all really,” he says without hesitation. “I was very keen on ploughing my own furrow and going to Nice was my own decision. It was important to me.

“I also knew that ITV and BBC were coming to Nice. This sounds odd to people now but athletics was on telly that week on Saturday, Sunday, Tuesday night in Nice, Friday night and then Saturday back on the BBC.”

He continues: “In Nice I was racing against Aouita and Cruz – the Olympic 5000m and 800m champions – so it was a big deal at the time. I’d run there a few times and had a good relationship with the organisers.

“I’d become a friend and a rival of Saïd, but Cruz was the new element as the Olympic 800m champion and everyone thought he had this big potential at 1500m. So Nice was delighted to have myself and Aouita, but they were really over the moon that Cruz had chosen this race as his first big 1500m run.”

As with several races that summer, Cram wasn’t particularly bothered what the early pace was, as long as it was fairly honest. “I hadn’t asked for any pace but then I heard that Cruz had asked for 2:20-21 through 1000m. It’s pretty quick but not super quick and I thought: ‘Why is Cruz determining what pace we run?’. I thought it was ambitious for him. The set-up of the race was for him and not myself and Saïd, which was ironic in the end.

“Cruz was up there in the early stages but at some point found the pace a bit hot and I was mainly over there to ‘race’. It certainly wasn’t a world record attempt but it just turned out that way.”

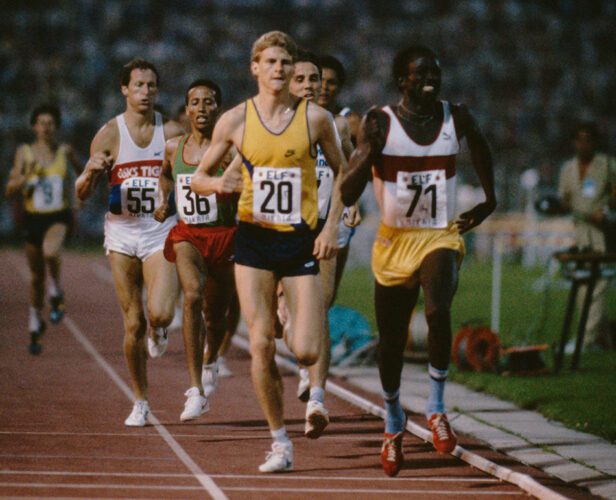

In warm and humid conditions, Babacar Niang of Senegal blasted through the first 200m in 26.86 with Cram almost a second behind and jostling with fellow runners to find a good position. Niang went through 400m in 54.36 with another pacemaker, Omer Khalifa of Sudan, behind. Cram followed in 55.5, then came Cruz and Aouita.

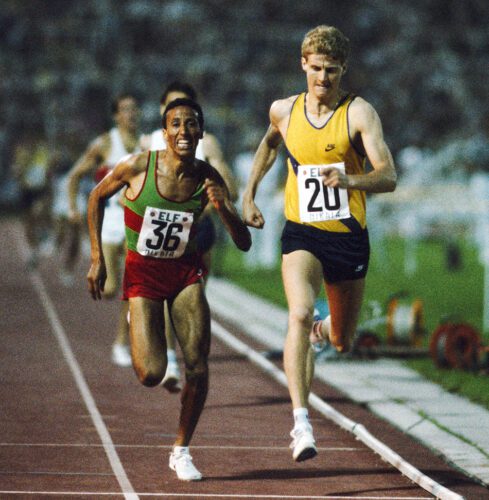

The second lap slowed to 59.3 as Niang hit 800m in 1:53.68. Khalifa then took over and went through 1000m in 2:21.89, with Cram close behind. As Khalifa hit the bell in 2:36.18, Cram decided to go for it. Wearing his yellow Jarrow & Hebburn singlet and with the number on his back having become partly unpinned so it flapped on to the back of his shorts, he let rip with a long run for home.

Jose-Luis Gonzalez of Spain was two metres behind with Aouita, crucially, having missed the break sat four metres back. Cruz, meanwhile, was a fast-dropping sixth – and would eventually wind up seventh in 3:37.10.

As Cram passed 1200m in 2:49.66 he had run the third lap in 55.8 and was now at least six metres clear of Aouita. Striding out majestically, the Briton was looking to make history with Aouita desperately scrambling to make up the deficit down the back straight and around the final bend.

Cram still held a decent lead into the home straight but Aouita closed with every stride during a frantic effort. At the line, Cram’s advantage was just four hundredths of a second, with the flailing Moroccan narrowly failing to catch him.

Cram’s last lap was 53.4 and his final 800m 1:50.2, with Aouita clocking 52.7 and 1:49.8 respectively. In third, Gonzalez smashed Jose Abascal’s Spanish record with 3:30.92 with Scott running an American record of 3:31.76 in fourth.

“I’ve watched the finest 1500m in history,” said Michel Jazy, France’s former world mile record-holder. “Aouita committed a monumental error in staying so far behind Cram. But one can only have admiration for Cram’s determination and courage.”

Cram remembers: “It was a hot and humid night and I won by the skin of my teeth. Saïd was very happy with his run, too. He was a fierce competitor but had a lot of respect for me, some of which was maybe a bit misplaced. It sounds a bit stupid but he was pleased he got so close.”

In doping control, Cram was dehydrated and had to drink two beers to help give a sample, which made him light-headed as he wasn’t a beer drinker.

“I then had a message from Primo Nebiolo, president of the IAAF, who was in the hotel in a suite and wanted to give me his congratulations. When I got there I immediately had some champagne shoved in my hand, which made me even more light-headed.

“It’s really hard to sleep after races anyway. When you’ve run well, it’s very hard. But when you’ve broken a world record, it’s almost impossible!

“We went out to get some food and I ended up playing the drums. Saïd was on the stage with me. It was a lot of good fun but we were up half the night and I was meant to be racing again on Friday.”

When Cram woke up on Wednesday after very little sleep, there were photographers around his hotel. “I called Andy Norman and told him: ‘I’m knackered, can you move our race from Friday to Saturday? I need another 24 hours as I still want to race’.

“In the end Seb still wanted to race Friday night over 800m and I did a mile on Saturday. I still wasn’t feeling great but I ran okay and managed to win.”

Cram has remained friends with Aouita and it amuses the Briton that whenever he visits Morocco he is often recognised and given special treatment at the airport “simply because I was the guy who raced Saïd Aouita”.

Their racing exploits have endured down the decades, too. Cram recently had a young intern from Morocco working at his Events of the North company and, when the boy realised Cram was an ex-athlete who had raced Aouita in the 1980s, he said: “Wow, you raced Saïd Aouita!?”

Cram says: “It’s interesting that Aouita seems almost more revered to some than Hicham El Guerrouj. Myself and Saïd had a healthy respect for each other and always seemed to get on okay. We were rivals but I always found him very easy to chat to.”

World record No.2 – Oslo, mile, 3:46.32

Following Nice, Cram enjoyed an easier mile victory at the Peugeot Talbot Games at Crystal Palace in 3:56.13 – with Coe winning his 800m the previous evening – before setting a UK all-comers’ record of 2:15.09 for 1000m at the Dairy Crest Games in Edinburgh, although Channel 4 abandoned its coverage of the meeting in Scotland due to anti-apartheid banners aimed at Zola Budd’s participation.

Four days later Cram was part of a Bislett Games meeting in Oslo that saw three world records fall, with Ingrid Kristiansen clocking 30:59.42 for 10,000m and Aouita running 13:00.40 to take one hundredth of a second off Dave Moorcroft’s 1982 mark.

“Remember I was just racing and not really training much in between,” Cram remembers. “I was taking at least a couple of days off and doing nothing after a race. It was like a severe case of DOMS. My calves were so sore but I still knew I was running well and I was full of confidence.

“Because I hadn’t raced Coe the previous Friday, he was keen to face me in the mile. So I went there with anticipation but not necessarily knowing what I was going to do. When they asked me about the pace, I told them I wasn’t really bothered as long as it was reasonable. Seb wasn’t stupid either, so he obviously felt he was in good enough shape to put up a good performance and beat me.

“There was no way I was going to take it on at an early stage, chase a time and allow Seb to sit on me, as he was the world record-holder, Olympic champion and very good at sitting on someone and coming past them in the closing stages.”

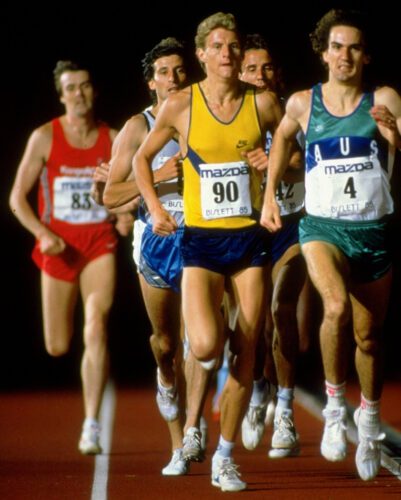

The Dream Mile was the last race of the night, starting at 11.26pm local time for the benefit of American television. This time American James Mays was the hare and went through 440 yards in 56.1 and 880 yards in 1:53.82 before dropping out after two-and-a-half laps.

Behind, Cram was always well placed but Coe had started slowly and it helped the double Olympic 1500m champion when the second pacer, Mike Hillardt of Australia, ran a slow third lap of 59.32 which meant he hit the bell in 2:53.14.

“On the third lap it suddenly felt like we were jogging,” Cram says. “All I remember was, as we approached the bell, I thought: ‘It’s Seb and I cannot leave this to the last 200m’. My strength was winding it up and Seb knew what was coming, too. I glanced at the clock, saw 2:53 and thought: ‘Jings that’s slow’. But I had this thing of taking things up a notch really going for it with 200m left. I don’t really ever look around but with 100m to go I sensed I was clear and I was flowing.”

Similar to Nice, Cram began to get into full stride with a lap to go but this time it was Coe, not Aouita, in pursuit. Unlike Aouita, Coe was in closer contact down the back straight but began to fall back with 200m to go as Gonzalez moved past him into second.

Cruising away, Cram covered the final 200m in 25.4 and the last lap of 53.0 as he clocked 3:46.31 – a time that would survive as the British record until Josh Kerr ran 3:45.34 in 2024.

“In Oslo the straights are really long and the noise was incredible,” says Cram. “Also the announcer was quite savvy and with 200m to go he realised the race was won and I think he said something to the crowd that suggested the world record was on.

“When I crossed the line I knew I’d run fast but I was a bit surprised it was that quick. As a miler I grew up reading about and meeting the Roger Bannisters and the John Landys and Peter Snells… and Derek Ibbotson was probably the first world record-holder I met when I was 17. So I’d had this thing about the world mile record since I was pretty young and all of that was wrapped up in my Oslo run.

“Nice was great but from a personal perspective breaking the mile record was a massive thing. For a Brit and for myself personally it had the whole heritage and the resonance of breaking the record. I’d broken four minutes as a 17-year-old and it had catapulted me career-wise so to break the world record about eight years later was great. My family had come over from Germany to watch as well and both my parents were there, which was a bit unusual as they didn’t come to that many meets.”

Magnanimous in defeat, Coe said: “Steve is obviously inspired… positively flying at the moment. His speed was awesome and I didn’t have a hope of catching him. It was his night.”

World record No.3 – Budapest, 2000m, 4:51.39

Coe had broken three world records in 41 days in 1979 but Cram was destined to manage his hat-trick in 19. The final piece of the jigsaw came during a gruelling five-lap effort in Budapest.

“I didn’t want to go for a 1500m or mile record again,” he says. “So I asked what else I could do. Someone said to me it was a soft record, which is absolute rubbish. It was held by John Walker [with a hand-timed 4:51.4] and I bought into the narrative that it was an easy record, which it definitely wasn’t, especially when I had no one to run against.”

As in Oslo, Mays set the early pace with 58.06 at 400m, with Rob Harrison moving into the lead at 800m in 1:55.73 and Cram three metres back.

Harrison dropped out at 1000m in 2:25.02, leaving Cram to run the second half alone, just as Walker had done in his record run in Oslo nine years earlier. With a 58.48 third lap, Cram passed 1200m in 2:54.58 and then ran a 59.34 to pass 1600m in 3:53.92.

“I was really hurting on the last lap and doing a time trial, which wasn’t really my strength,” he recalls. “I preferred racing people. As much as 800m runners think they can run 1000m but find out they can’t, the milers often think they can run ‘only another lap’ and do a good 2000m.

“I had no-one to race and I was a racer. I wasn’t very good at racing against the clock. I needed the person to beat.

“I got to the bell and thought: ‘I’m tired here!’ The stadium was a large expanse of space and it wasn’t very full. With 200m to go it felt like I was out in the wilderness and I found it very tough.”

Cram finished with a 57.47 final lap but with the timing device on the TV screen showing 4:51.40 and the trackside clocking displaying 4:51.46, for several minutes it was felt Cram had missed the mark. That was until the photo finish analysis revealed he’d run 4:51.39.

“If I’d had a decent set-up I probably could have run a couple of seconds quicker and these days I’m not surprised people can run 4:45,” he says. “I’d been so led to believe it would be an easy world record, I couldn’t even remember what the tenths of a second were!”

Cram’s clearest memory of the event, though, comes from a press conference. “I was sitting with Sergey Bubka and Jarmila Kratochvilova and there were maybe 15-20 members of the British press there because of what I’d done that year. When it came to my turn to answer questions, I’d seen this head pop up above everyone else at the back of the room and it was Tim Rice.

“Tim and Andrew Lloyd Webber were massive at the time so I picked him out and all the British sports journalists looked around to see who I’d picked.

“He asked a sensible question and I answered it and later I made a beeline for him and asked him what on earth he was doing in my press conference. It turned out he was promoting Cats and staying in my hotel. He said he loved athletics and saw the sign for the press conference but he was mainly keen to tell me he was a boyhood Sunderland fan.

“Today I see him a few times every year and he’s become a good friend and he sits on our foundation. I remember Budapest more for that incident than the actual race!”

End-of-season victory and defeat

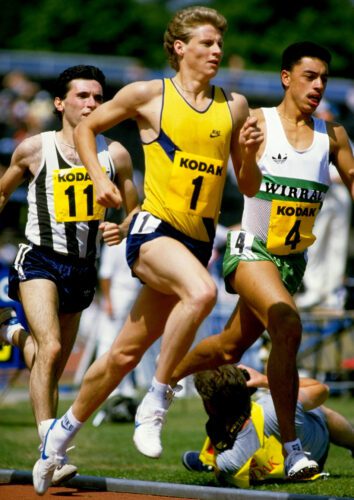

Five days after Budapest, Cram produced a near-record run that was every bit as impressive when he narrowly missed Coe’s 1000m mark of 2:12.18 in blustery conditions in Gateshead.

“After the 1500m, mile and 2000m, I thought: ‘Let’s have a go at the 1000m record at Gateshead’. But it was such a windy day,” he says.

In effort to avoid the worst of the wind, Cram asked for the race to be moved from its scheduled 8.35pm to 9.50pm, which meant it was shown on Channel Four instead of ITV. “The decision backfired, though,” Cram says, as the wind dropped briefly when the race should have taken place, only to pick up again at 9.50pm, by which time it was also colder.

“Again I got left on my own a bit too, which is understandable at that pace,” he remembers about a race where Mays again took the pace through 400m in 51.55, with Cram third in 51.8. With Rob Harrison due to take over as the second pacer, Cram simply went past at 600m (78.84), passing 800m in 1:44.94 and then struggling over the last 200m in 27.91 to clock 2:12.85.

“For half a second I thought I’d done it as the clock they used in Gateshead was a bit different,” he says, “and the final two digits took a moment before they flipped from zero-zero to 88. I knew I was close but down the back straight I’d been fighting the wind so much. I still consider it one of my better runs as it was a hell of a record.”

After an emphatic victory over 1500m in the European Cup final in Moscow, Cram moved on to Zurich to take on Cruz over 800m – and scored another big win as he passed the Brazilian in the home straight to run 1:42.88.

“Some of the races I’m most proud of are not 1500m or mile races and that 800m in Zurich is a good example,” he says. “Against Cruz I went out a little harder than I would normally.

“I was in Davos in Switzerland for a few days before the race and was doing some 200s that were pretty quick at altitude. At the start of an 800m I’d struggle to keep up usually if they went through 200m in 25 seconds as that would be me flat out! But on this night they went out in about 50 seconds and I was maybe 51 and bits which was perfect for me as I liked to run even paced laps.

“Cruz was bloody good and he was a big lad to get around. We had a good battle down the home straight and I just had a little more strength to go past him.

“From the first Oslo race to the 1:42.8 in Zurich was probably about seven weeks with hardly any training.”

The lack of training caught up with Cram in the end, though, when he was beaten by Ovett in the Westminster Mile on the roads in mid-September.

“I’d kind of knocked it on the head by then training wise,” he says. “It was almost as if I’d banked up all this training that was petering out as the season went on. It was the first Westminster Mile and it was televised and they were very keen I did it. Most people don’t remember it and that’s okay with me!”

As we prepare to wrap up our interview, Cram is rushing a little to get to Leeds to help some athletes with their training. Four decades after his great performances, he is still regularly found trackside or at cross-country races passing on advice and inspiration to the next generation.

Looking back at ’85, he says: “It was a great time, great fun, fond memories, a lot going on behind the scenes and it set things up in a nice way. But when I look back at it they were iconic races for me and for a lot of people watching and ended up being the fastest I ran.

“I’m fairly sure I could have run quicker – I was maybe in better shape in 1986 – but I had two championships and then got a couple of niggles, so it wasn’t to be.”

Cram’s summer of 1985

June 21 – McVities Challenge, GB vs USA, 800m, Birmingham

1 S Coe 1:46.23; 2 S Cram 1:46.46; 3 S Redwine (USA) 1:48.18

June 27 – Oslo Games, 1500m, Norway

1 Cram 3:31.34; 2 S Scott (USA) 3:34.58; 3 J Spivey (USA) 3:35.15

June 29 – GB vs TCH vs FRA, 800m, Gateshead

1 T McKean (GBR) 1:47.25; 2 Cram 1:47.61; 3 G Philipe (FRA) 1:48.54

July 13 – AAA Champs, 800m heats, Crystal Palace

1 Cram 1:47.77; 2 E Koech (KEN) 1:47.89; 3 T Morrell (GBR) 1:48.39

July 16 – Nikaia Meet, 1500m, Nice, France

1 Cram 3:29.67; 2 S Aouita (MAR) 3:29.71; 3 J-L Gonzalez (ESP) 3:30.92

July 20 – Peugeot Talbot Games, mile, London

1 Cram 3:56.13; 2 G Staines (GBR) 3:59.24; 3 P Chester (GBR) 3:59.60

July 23 – Dairy Crest Games, 1000m, Edinburgh

1 Cram 2:15.09; 2 D Mack (USA) 2:16.90; 3 A Bile (SOM) 2:17.15

July 27 – Mazda Bislett Games, mile, Oslo

1 Cram 3:46.32; 2 Gonzalez 3:47.79; 3 Coe 3:49.22

Aug 4 – Budapest Grand Prix, 2000m, Hungary

1 Cram 4:51.39; 2 S Cahill (GBR) 5:02.35; 3 U Bergmann (GDR) 5:02.46

Aug 9 – Kodak Classic, 1000m, Gateshead

1 Cram 2:12.85; 2 P Dupont (FRA) 2:19.90; 3 P Thiebaut (FRA) 2:20.24

Aug 18 – European Cup, 1500m, Moscow

1 Cram 3:43.71; 2 O Beyer (GDR) 3:44.96; S Mei (ITA) 3:45.14

Aug 21 – Weltklasse, 800m, Zurich

1 Cram 1:42.88; 2 J Cruz (BRA) 1:43.23; 3 J Gray (USA) 1:43.43

Sept 15 – Westminster Mile, London

1 S Ovett 3:56.1; 2 Cram 3:57.7; 3 R Flynn (IRL) 3:58.0

Durham City Run Festival

Steve Cram once joked he “could write a book on the 1985 season alone”. In the absence of such a publication, you’ll have to make do with our feature here or instead you can go and listen to Cram chat about his world records at the Durham City Run Festival at the Gala Theatre in Durham on July 16. See durhamcityrunfestival.com