On March 31, 1973, unheralded heavyweight contender Ken Norton outpointed Muhammad Ali to score a huge upset. Seven months later, Ali scored a close decision victory of his own in the rematch. The loss did not adversely affect Norton’s fortunes; seven months later he faced heavyweight champion George Foreman. But against the power-punching Texan, Norton didn’t even make it through the second round, the champion demolishing him with a series of brutal haymakers. Foreman’s next title defense would be one of the most extraordinary championship fights in the sport’s history, when the following October he faced Ali in Kinshasa, Zaire.

All this to say, if Ali vs Foreman is to be fully understood, one must consider the bout’s context. It is a lesson in matchmaking, publicity, and the inter-relatedness of boxers’ careers. The drama and emotion of “The Rumble in the Jungle” was possible only because of the litmus test Ken Norton provided its two combatants. In losing to Norton, Ali failed this test before he passed it, while Foreman breezed through with frightening ease. These results are necessary plot elements in one of boxing’s most famous stories, which climaxed with Ali’s astonishing victory over Foreman and his reclamation of the undisputed heavyweight championship of the world.

Prior to his first meeting with Ali, Norton was perceived by most as an easy tune-up for the former champion. But when the two squared off in San Diego, it was obvious the 28-year-old Norton had paid no heed to the opinions of odds-makers. He had reason to be confident. While he couldn’t match Ali’s experience, he had Eddie Futch in his corner, the man who had helped guide Joe Frazier in his victory over Ali two years earlier. He was also tall, with an excellent left jab, and in the second round Norton used it to tag Ali on the chin, snapping his head back. The punch surprised those at ringside and demonstrated the contrast of energy between the two. While Norton was obviously primed and ready to rumble, Ali was sluggish from the outset, standing upright and landing occasional shots but no devastating flurries.

Starting in round three, Ali, having realized Norton presented a serious challenge, began to make better use of his lauded footwork, which allowed him to control the ring. This tailed off however, while trainer Angelo Dundee rationalized Ali’s spiritless performance to Howard Cosell as being part of some nebulous plan to wear Norton down. That didn’t happen. Norton continued to be the aggressor and for the entire contest he was the sharper and more focused boxer. In the last round he backed Ali into a corner and hammered him with a hard right. When the final bell rang the hometown San Diego crowd gave Norton a raucous ovation.

Before the ring announcer had even given the result of the split decision, an egotistical Cosell, sensing another opportunity to impose himself on the television audience, broke the news that Norton had won. Afterwards he verbosely relegated “a broken Ali” to the dustbin of “fistic history.” If only Muhammad had been able to answer back; alas, Norton had broken his jaw. After congratulating his conqueror, Ali walked off to his dressing room, for once, silent.

It was a shocking upset, confirming for many Ali’s decline. But Norton agreed to a rematch and in September Ali reversed the earlier result by winning a split decision of his own in a very close fight. Ali was so impressed with the ex-Marine’s ability that afterwards he stated that, “Norton is a better fighter than any I’ve fought, except maybe Joe Frazier.” Ali then won a decision over Rudi Lubbers before avenging his first career defeat by outpointing his greatest rival, Frazier, thus setting up perfectly the historic showdown with Foreman.

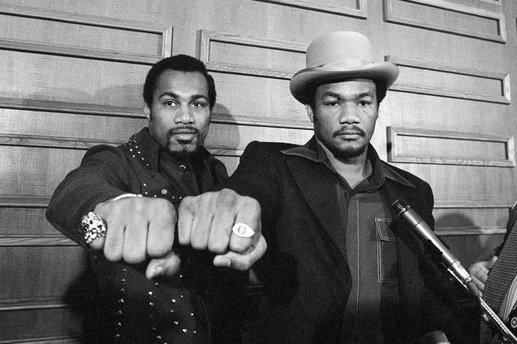

Meanwhile, Norton had earned wide respect for his showings against a man considered one of the best heavyweights of all-time and he didn’t have to wait long for another golden opportunity. His next fight was against the undefeated and undisputed heavyweight champion, George Foreman, the man who had demolished Frazier with frightening ease. The match was held in Caracas,Venezuela, and became known as much for the bizarre financial odyssey that attended it as the actual outcome.

If Caracas seems like a strange destination to hold a heavyweight boxing event, there was a practical reason it was sought out as the host: an agreement had been reached stipulating all taxes would be waived. However, the night before the fight, Howard Schwartz, vice-president of the Video Techniques outfit broadcasting the match, received a memo from the Venezuelan government stating that indeed, some taxes would be assessed. This caused much consternation for the organizers, but the following day Schwartz was assured the original agreement would be honored.

In spite of these dealings behind the scenes, Foreman vs Norton went ahead as scheduled. Big George came in twelve pounds heavier than Norton, but he had one unquantifiable advantage, that being his reputation for annihilation. Heavyweights whose modus operandi is to destroy their opponents by sheer force have an aura that separates them from those who simply box. Their opponent’s doom seems inexorable. Like Mike Tyson after him, and Sonny Liston before, the focused Foreman had this quality in spades. Even though Norton didn’t look demonstrably different—he was the same height and heavily muscled—he seemed composed of putty compared to Foreman’s iron. By fight night, his destruction appeared inevitable.

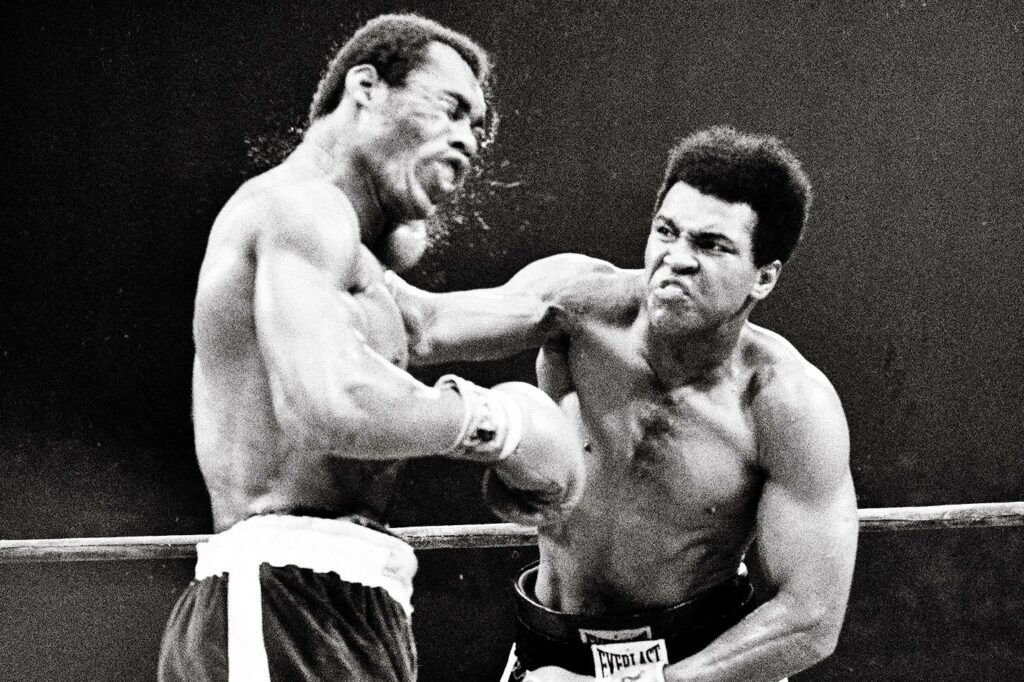

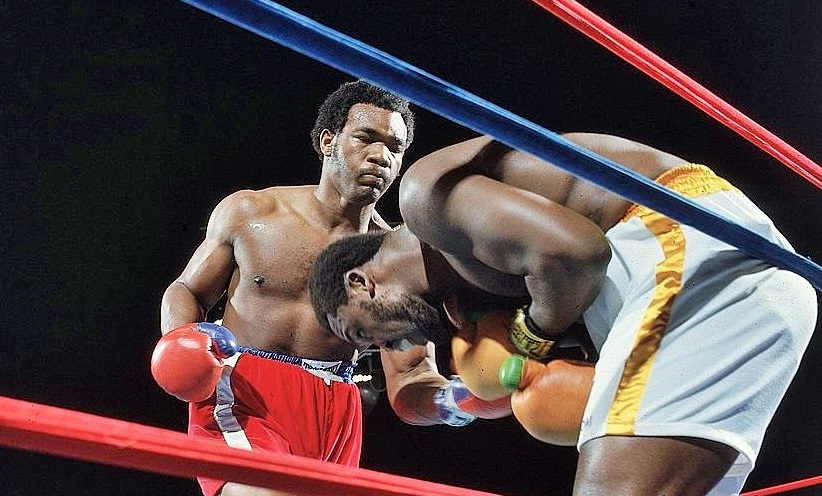

In the opening round, Forman stalked a circling Norton. After some tentative jabbing, Big George, backed Norton to the ropes and let loose with his heavy artillery. Watching this version of Foreman now, his style is striking. He throws punches with wide, wild swings, leaving himself unprotected in the process, his fists starting low and ending high, like a softball pitcher. Unorthodox, almost clumsy looking, this manner of fighting must be backed up with awesome power, and in Foreman’s case it was. And before the end of the opening round, George’s heavy swings began to find their mark.

Between rounds, long time boxing play-by-play man Bob Sheridan cut to his ringside commentator who had been silent up to that point. It was Muhammad Ali, and his ‘analysis’ was essentially self-praise. Ali spoke bombastically about Norton, with whom he had fought twenty-four tough rounds, stating that anyone who could do that against him was nothing short of great. He commented that Foreman, who was simply a ‘good amateur’, wasn’t going to stop Norton because Ali himself couldn’t do it. The Greatest’s insecurity was on full display here, and he even began yelling instructions at Norton’s corner, so invested was he in not having his reputation suffer in comparison to Foreman’s if the champion scored a knockout.

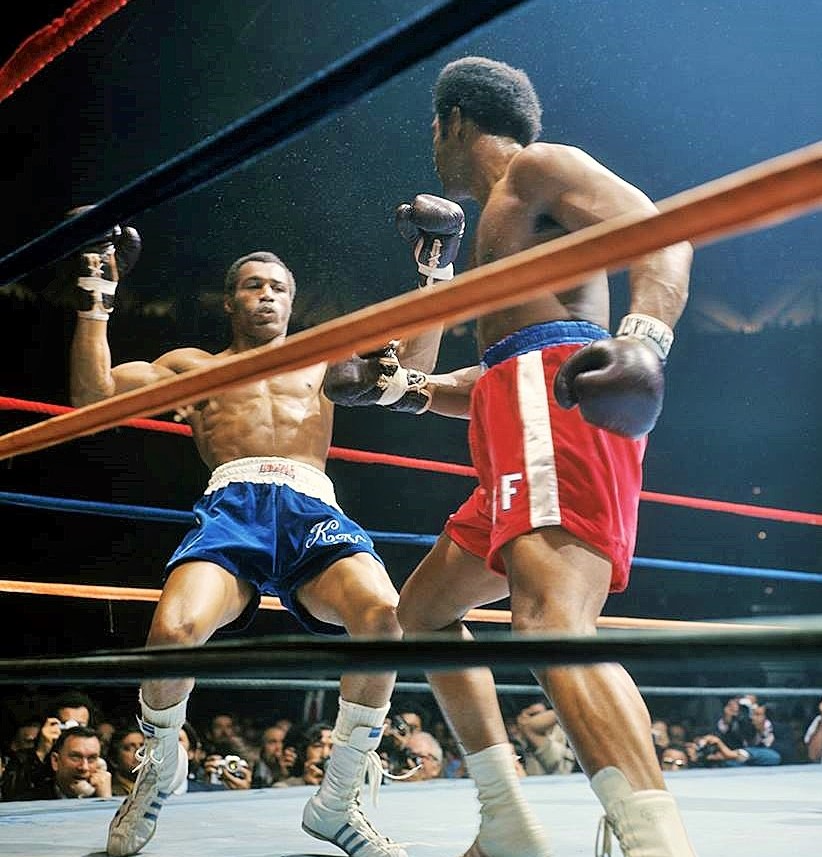

Norton started the second effectively when he slipped one of Foreman’s shots and landed a left hook but the champion was undaunted and continued his methodical stalking. Then Foreman’s right fist took over. He walloped the challenger with four consecutive right hand bombs, leaving a dazed Norton collapsing into the ropes. He beat the count but had barely any time to compose himself before the relentless Foreman attacked again, scoring another, albeit less devastating, knockdown.

The referee had to forcibly push the ferocious champion away to give the damaged boxer some space, and again Norton got to his feet. It would be the last time. A straight left set up a horrific uppercut and a series of more sledgehammer blows, and once again a dazed Norton fell to the canvas. He laboriously tried to raise himself, holding onto the ropes for support, clearly finished, as the referee counted and his cornermen entered the ring to signal surrender.

This fight has since become known as the ‘Caracas Caper’, because afterwards the Venezuelan government reneged on its tax-free promise. Both fighters were held in the country for several days. Foreman even had to pay back some $300,000, over half of his purse, before he was allowed to leave on April 2.

George Foreman had now obliterated the only two men to have beaten Muhammad Ali, and in both instances the victories were so comprehensive, so shattering, that most thought Ali would meet a similar fate against such a powerful champion. The most vocal believer in Foreman’s superiority was Ali’s equal friend and foe, Howard Cosell. In the weeks leading up to Zaire, he made his thoughts public, reflecting the opinions of so many. Cosell was instrumental in framing the narrative of “The Rumble in the Jungle,” casting the older Ali as a huge underdog to the awesome puncher who had stopped Frazier and Norton with such frightening ease.

Of course, Ali saw things differently, and would carry through with one of the most brilliant performances in heavyweight history. Aside from its thrilling action, the upset win was so exhilarating because Ali refused to play the role assigned to him in the story of George Foreman’s ascent, a story made possible by Foreman’s knockouts of Frazier and Norton and Ali’s losses to both men. Boxing matches never stand alone and cannot be divorced from past events or future matches. And yet, casting aside the implications of the past is how Ali stepped outside of the narrative that was imposed on him, leading him to once again shock the world and achieve one of the greatest victories in boxing history. — Eliott McCormick