That first historic Ali vs Frazier confrontation in 1971, without question one of the biggest sports events of all-time, took a significant toll on both “Smokin’ Joe” and “The Louisville Lip”. Months of build-up and intense pressure were topped off by a fierce, dramatic, fifteen round war which saw Frazier, in one of the greatest performances in boxing history, earn a unanimous decision win. But following the titanic struggle, Joe was admitted to hospital and treated for a number of ailments, including hypertension, and he would never be quite the same fighter ever after.

Ali did not pay as steep a price physically, though he too visited a hospital to treat an injured jaw, but in absorbing his first career defeat his public image sustained some serious damage. No longer was Muhammad Ali the uncrowned king who had been unjustly stripped of his crown after refusing to serve in the military. Instead he lost his claim to supremacy after being knocked down and beaten fair-and-square by an equally exceptional talent. He was now, truly, a former champion.

And by the time of Ali vs Frazier II, so was Joe. After a couple of wins against overmatched opposition in 1972, Frazier took on a young contender named George Foreman, the 1968 Olympic gold medalist, undefeated with 34 knockouts in 37 wins. Having vanquished Ali, Frazier was viewed as a truly dominant champion and there was little reason to think Foreman might take the crown. So fight fans got the shock of their lives when Big George not only defeated Frazier in Kingston, Jamaica, but gave him a terrible beating, knocking him down six times in less than six minutes as Howard Cosell repeatedly bellowed from ringside, “Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier!”

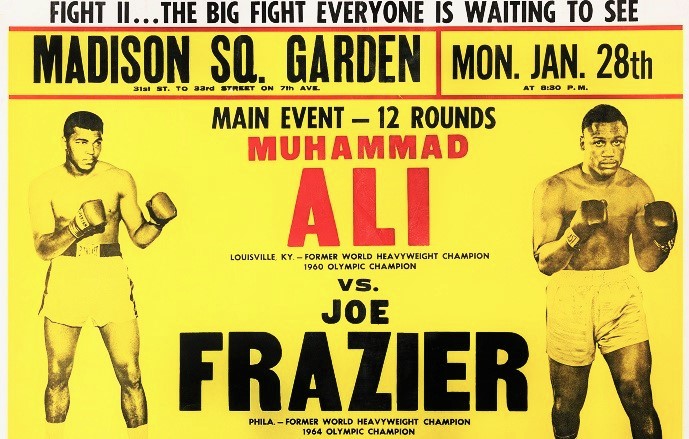

During this same interval, Ali had kept a busy schedule, ten bouts over eighteen months, before suffering his own setback just two months after Frazier lost to Foreman, a twelve round decision loss to a young, unheralded contender named Ken Norton. Worse, Ali suffered a broken jaw during the fight and was out of action for months while it healed, though both Ali and Frazier got back in the win column before the year was out. Joe took a clear-cut points verdict over rugged Joe Bugner in July, and Ali squeaked by with a revenge split-decision win over Norton two months later. And so the stage was set for a high-stakes, non-title rematch between Frazier and Ali, the winner to get a shot at Foreman.

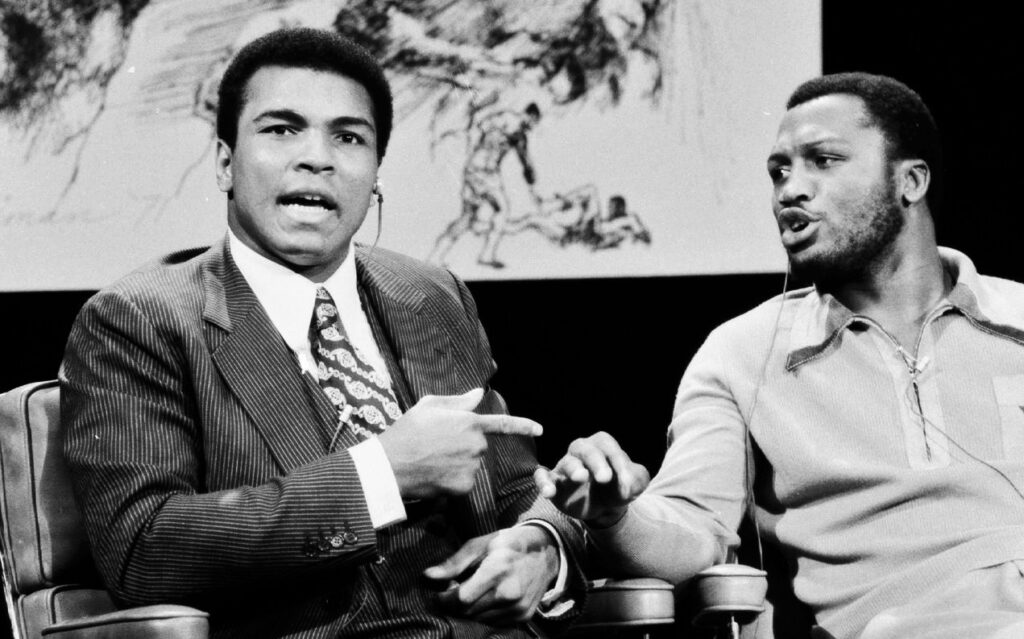

Long before this many wondered why Ali vs Frazier II had not already taken place. After the extraordinary success of their first encounter, it seemed a safe bet that a rematch would happen before too long. But the months passed and the champion showed no interest. The reason was simple: Frazier hated “Clay,” as he liked to call him. During Ali’s forced exile Frazier had worked to help his rival regain his boxing license and had even loaned him money. But once contracts were signed for the ’71 bout, Ali, seeking to establish a psychological edge, had mocked and taunted Frazier, calling him “ugly” and “ignorant” and labeling him an “Uncle Tom.” To Frazier, this was betrayal. And it hurt. Such was Joe’s fury that, according to his own account, he prayed in his dressing room before their first showdown for the power to literally kill Ali.

So not surprisingly, when anyone tried to discuss a rematch, they didn’t get very far with Joe. He had deeply resented the even purse split for the first fight and so Frazier’s response regarding a return was simple and to the point: show me the cash. Before the Foreman bout there had in fact been discussions about putting together Ali vs Frazier II with the fighters evenly splitting a six million dollar pot, just as they had split five million in ’71. “No way,” said Frazier. “I’m the champ. I won. I’ll go to hell before I give him half again.” So instead of fighting Ali for three million, Joe got pummeled by Foreman for less than one.

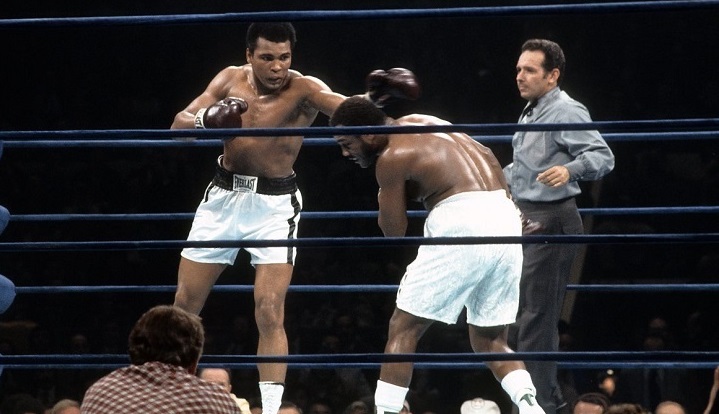

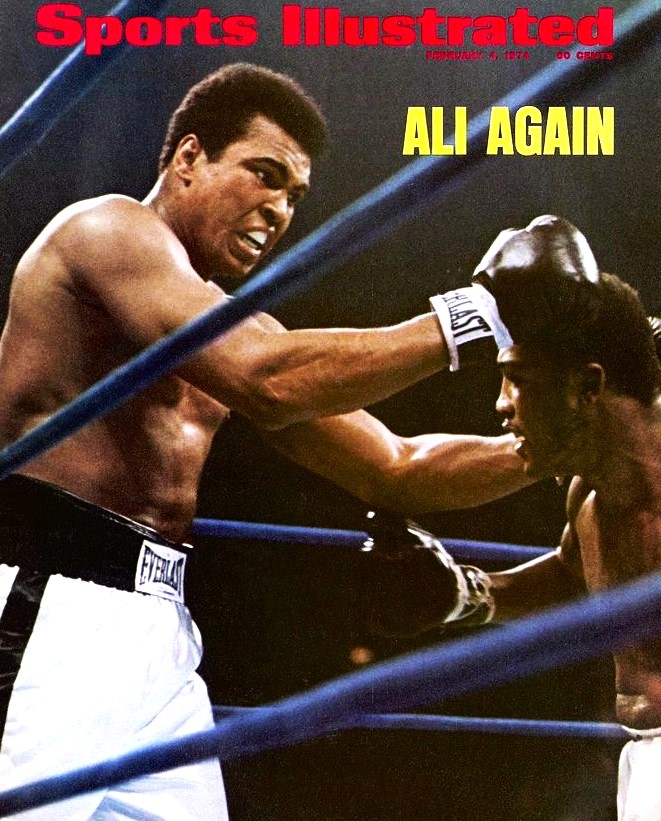

Madison Square Garden was sold out again for Ali vs Frazier II but the atmosphere was nothing like ’71. How could it have been? The first fight was history, a contest between two undefeated heavyweight champions, viewed by an estimated three hundred million people around the globe. Now Ali and Frazier were no longer bigger than life, but instead ex-champions, older and slower. Yet the tension between the two was, if anything, even greater. None of Frazier’s resentment had abated, something clear to all when Joe tried to wring Ali’s neck during a live television interview with Howard Cosell. So by fight night, while it wasn’t ’71, anticipation still ran high.

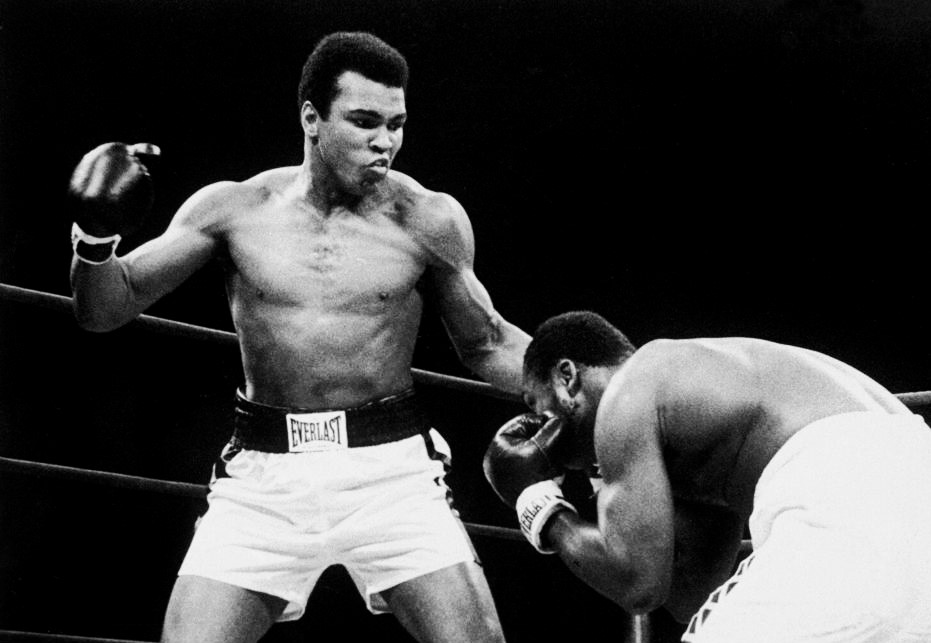

Unfortunately for Frazier, Ali refused to make the same mistakes which had abetted Joe’s efforts in ’71, such as clowning and playing to the crowd while Joe piled up points, or settling on the ropes and letting Frazier pound his abdomen. He also refused to engage in as many spirited, toe-to-toe exchanges; the second it looked like a firefight might break out, Ali clinched or got on his bicycle. Concentrating on lateral movement and using the entire ring, Ali circled and danced, landing quick jabs and one-twos, and hugging Joe anytime he threatened. It didn’t make for thrilling action, but it did allow Ali to establish a commanding lead on the scorecards as he swept the first four rounds, even staggering Frazier in the second with a right hand.

But it must be noted that Ali was helped by the fact that Frazier appeared a pale imitation of his formerly “smokin’” self. Compared to the first fight, Joe moved with less urgency and his punches lacked snap. He pursued doggedly, occasionally getting home with the big left, but for the most part Ali the matador stayed one step ahead of the bull on legs more nimble than in ’71. And when Joe did threaten, Ali tied him up and hung on until the referee intervened. In the fifth the pace slowed and Frazier started to close the distance but Ali kept clinching while moving just enough to stay out of trouble. The sixth was controlled by Ali and a frustrated Frazier taunted “The Louisville Lip” before paying for his trouble by eating a sharp one-two.

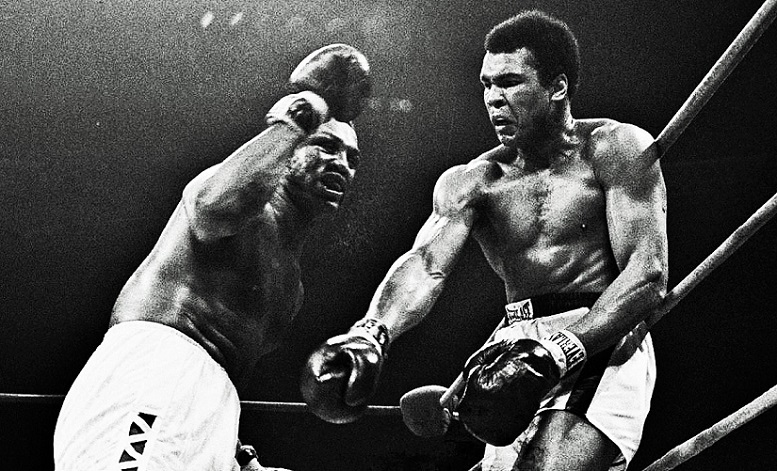

It was not until the seventh that Frazier finally found some fire and smoke, timing Ali better and landing his howitzer, the left hook, repeatedly. He took the eighth as well but still, he could not seize control of the contest as he had in ’71; Ali’s clinching tactics blunted his attack. And then in the ninth Ali came back to life, launching swift forays of one-two’s and right hands, beating Frazier to the punch repeatedly, and stunning him with an uppercut at the end of the round.

Now it was obvious that Frazier needed a knockout to win. And while Joe landed more left hooks in the tenth, unlike in their first clash, none seriously hurt or staggered Ali. Both men connected in the eleventh, the best action round of the fight, and in the final stanza Ali closed the show, throwing one flurry after another and giving the crowd the “Ali Shuffle” as he swatted at Frazier. And yet it was clinches, not punches, which allowed Ali to control much of the action and fittingly, as the final bell sounded, it found the two heavyweights tangled up in each other’s arms.

The contest had lacked the intensity, the drama, and the ebb and flow of their first historic duel and this time there was no suspense in terms of the outcome; Ali had clearly won no fewer than seven rounds. Frazier and his trainer Eddie Futch would complain about the referee’s unwillingness to penalize “The Greatest” for his constant holding, but Joe had simply not been busy enough to engender much sympathy. It had been a very good heavyweight fight, yet a somewhat anti-climactic affair, certainly not a classic, and now attention shifted to the prospect of the crafty Ali challenging the indomitable Foreman in the famous “Rumble In The Jungle.” — Michael Carbert