It is not for nothing that late scribe Jimmy Cannon called boxing “the red light district of sports.” Pugilism is no stranger to corruption and criminals and over the years the credibility of many bouts has been seriously questioned. Famous examples include the second Jack Sharkey vs Primo Carnera match; Jake LaMotta’s upset loss to Billy Fox; Johnny Saxton’s gift decision over Kid Gavilan, and Bruce Seldon hitting the deck after Mike Tyson missed him with a left hook. But the historic match between Jack Johnson and Jess Willard in Cuba for the heavyweight championship of the world is something different. This is the rare instance where a boxer claimed a fight was fixed, when in fact it was free of any chicanery whatsoever.

That said, it’s not difficult to understand the motivation behind Johnson’s claim that his defeat to Willard was not legitimate. “The Galveston Giant” was renowned for his technical skill and ring smarts. To lose his world title to a fighter widely viewed as not being in in his league must have been exceptionally painful for a man as confident and proud as Johnson clearly was. Thus, years after the fact, he invented an elaborate explanation for his unlikely downfall, a defeat which at the time had shocked the boxing world. Indeed, Willard’s victory remains one of the biggest upsets in the sport’s history.

Johnson, boxing’s first black heavyweight champion, won the title in 1908 and went on to outrage the public with his refusal to abide by the expectations of both polite society and a racist America which regarded black people as second-class citizens. Instead he did what he damn well pleased: flaunting his wealth, raising hell, and openly carrying on with white women, even marrying more than one. Had he not been heavyweight champion of the world, Johnson would likely have been murdered in an America that still lynched black men for far less.

Instead, there were repeated campaigns to find a “Great White Hope” to set things right, the term itself inspired by Johnson’s shocking reign. The most notable example is of course the first “Fight of the Century” between Johnson and former champion James J. Jeffries in July of 1910. It remains one of the biggest and most significant bouts in boxing history, albeit for all the wrong reasons, and while white America steadfastly believed the Caucasian challenger would put an end to their national nightmare, instead a grinning Johnson dominated and humiliated Jeffries, the much ballyhooed bout a complete mismatch. A humbled Jeffries was rescued in round fifteen, an outcome that sparked violent race riots across the country, and Jeffries himself later confessed that even in his prime he could never have bested Johnson.

But this result did not stop people from finding some way to persecute a black heavyweight champion who, unlike Joe Louis a few decades later, continually mocked the expectations of white society. In 1912 he was arrested and charged under the Mann Act, a racist law which effectively criminalized inter-racial couples and disallowed black men from traveling with white women. He was convicted the following year and Johnson promptly skipped bail, leaving America to travel in Europe and South America. In exile he had few chances to defend his world title, and so when he was approached by some American businessmen with a lucrative offer to face Willard in Cuba, Johnson accepted.

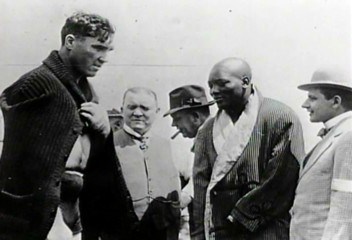

Like Jeffries before him, Jess Willard, “The Pottawatomie Giant,” was another “white hope” brought forward to reclaim the heavyweight title for the “superior” race. As his nickname suggested, Willard was huge; he weighed 245 pounds, stood over 6’6, and had a reach of 83 inches. He also possessed a powerful right hand and stamina which few heavyweights could match, a factor that proved significant against Johnson. Despite this, virtually no one anticipated a Willard victory. The primary appeal of the event was its being a rare opportunity to see in the flesh the famous champion, as Johnson had not defended his title anywhere close to the United States for almost three years. The widely held view was that Willard lacked the skill to compete with Johnson and another “Great White Hope” was about to fall.

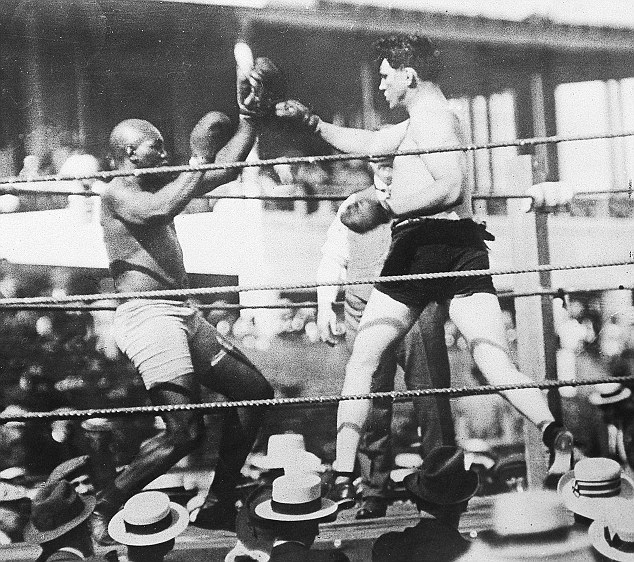

Johnson vs Willard, scheduled for 45 rounds, was held in Oriental Park in Havana on a bright, scorching hot day. The champion started fast and in the early rounds landed a number of punishing blows. At times, Johnson toyed with his opponent, even laughing at Willard’s lack of ring smarts and technique. In the seventh, he went for the knockout, pinning the hulking challenger in a corner and punishing him with hard shots for the rest of the round. For the most part, Johnson dominated the first twenty rounds, but the tough Willard remained on his feet, and two things soon became clear: the challenger would not quit, and the champion was tiring.

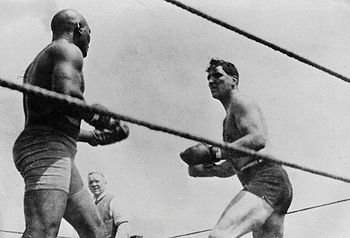

From here on the pace slowed and the momentum shifted. Now it was Willard who applied pressure as Johnson stood on increasingly shaky legs; the champion’s taunts, laughs, and grins vanished. In the 25th round Willard landed a thudding right hand to the chest, knocking the wind out of the champion. Exhausted and hurting, Johnson reportedly told his corner before the bell for round twenty-six, “Take my wife away … Tell her I’m awful weak and I want her to leave.” His spouse’s abrupt departure would serve as a pretext for Johnson’s later claims of having taken a dive.

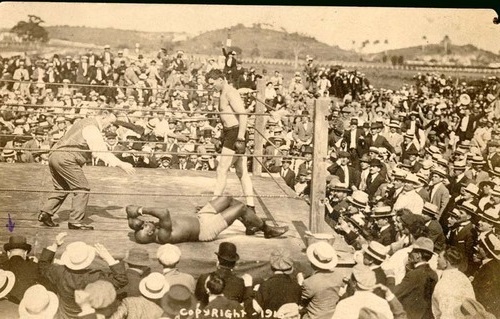

As the bell rang for what would be the final round, a clearly spent champion rose slowly to his feet. Willard pursued, landing several punishing blows, before connecting with an overhand right to Johnson’s chin that sent him tumbling to the canvas. The champion lay on his back and barely moved as the referee counted him out. The long battle was over and with it, the tumultuous and historic championship reign of Jack Johnson. To the surprise of everyone, Jess Willard was the new heavyweight king.

Initially, Johnson was gracious in defeat. In the ring he pulled Willard aside and wished him luck, telling him to take care of himself and his money. But as time passed, he became bitter. He first complained of not being fully compensated for the match, before making the claim that he had lost on purpose in exchange for a pledge that he could return to the U.S. and avoid criminal charges.

No hard evidence of any such agreement has ever surfaced, but Johnson held to this story for the rest of his life, even writing a lengthy “confession” on how he threw the match, which he sold to Nat Fleischer of Ring magazine. He claimed the reason the dive happened in round twenty-six was that he was waiting for a sign from his wife that the agreed upon sum of fifty thousand dollars was in her possession. Once she had the money, an exchange of signals took place and she left the stadium. The champion then lay down and took the count.

Johnson’s claims have never been taken seriously by boxing historians. As Willard himself said, “If Johnson throwed that fight, I wished he’d throwed it sooner. It was hotter than hell down there.” The story is full of holes, not least of which is the fact that in the early stages of the match “The Galveston Giant” was clearly risking a knockout of Willard. Why would Johnson dominate and batter an opponent if he intended to throw the fight?

As the bout’s referee, Jack Welch, stated: “In the thirteenth and fourteenth, I was almost sure Johnson would knock Willard out, but Willard showed that his jaw and body were too tough. Johnson put up a wonderful fight to the twentieth round, but age stepped in then and defeated him.” Welch went on to claim that he had in fact witnessed Johnson bet money on himself to win.

Years later, promoter Jack Curley stated, “Nobody ever took Johnson’s charges of fakery seriously. He was well past his prime, fat and dissipated, and he was worn down and knocked out by a strong, game and well-conditioned opponent.”

Of course the unfortunate victim of Johnson’s highly questionable claim was Willard. He has never received the full credit he deserved for beating the great Jack Johnson, a fighter regarded as one of the finest heavyweights of all time. Instead, Willard is best remembered for the savage beating he took from Jack Dempsey in their historic meeting on July 4, 1919. As for Johnson, he would return to the United States in 1920 to spend a year in jail, after which he continued to box, but he never again fought for the heavyweight title. — Robert Portis